Leonardo

on the Bible

"From Da Vinci's notebook on polemics and

speculation," Teabing said, indicating one quote in particular.

"I think you'll find this relevant to our discussion."

Sophie read the words.

Many have made a trade of delusions

And false miracles, deceiving the stupid multitude.

- LEONARDO DA VINCI

"Here's another," Teabing said, pointing

to a different quote.

Blinding ignorance does mislead us.

O! Wretched mortals, open your eyes!

- LEONARDO DA VINCI

Sophie felt a little chill. "Da Vinci is

talking about the Bible?"

Teabing nodded.

(Chapter 55, pp. 230-231)

Actually, Leonardo

is not 'talking about the Bible' here at all. Whether deliberately,

through laziness or through complete ignorance, Brown has taken

these two quotes out of context and is presenting them as meaning

something they definitely do not mean.

The first quote

is Section 128 of Leonardo's Notebooks. This passage and the one

before it (Section 127) come under the heading 'Against Alchemists'.

Section 127 reads: "The false interpreters of nature declare

that quicksilver is the common seed of every metal, not remembering

that nature varies the seed according to the variety of the things

she desires to produce in the world." The 'false interpreters

of nature' are clearly alchemists, as are those who have 'made a

trade of delusions'. Put back in their context, the idea that this

is somehow referring to Christianity or the Bible is clearly complete

and utter nonsense.

The same can

be said of the second out-of-context quote. It is one of a number

on the deadly nature of ignorance and any wasting of the intellect

- Sections 1165-1182. They include other sayings such as "Just

as iron rusts unless it is used, and water putrefies or, in cold,

turns to ice, so our intellect spoils unless it is kept in use."

(1177) and "The greatest deception men suffer is from their

own opinions." (1180). None of these related sayings have anything

at all to do with the Bible and there is absolutely no reason to

think that they are even hinting at anything to do with Christianity

or religion at all.

Back

to Chapters

The

Formation of the Christian Bible

Teabing cleared his throat and declared, "The

Bible did not arrive by fax from heaven."

"I beg your pardon?"

"The Bible is a product of man, my dear.

Not of God. The Bible did not fall magically from the clouds. Man

created it as a historical record of tumultuous times, and it has

evolved through countless translations, additions, and revisions.

History has never had a definitive version of the book."

(Chapter 55, p. 231)

This is more

or less correct, as far as it goes. Throughout the novel, however,

Brown has his characters speak of the Bible as though it is a single

book. In fact, the Bible is a collection of many books, though it

is generally printed and bound in one volume these days for convenience's

sake. Before the advent of printing, single volume Bibles were extremely

rare on account of the expense involved in making and copying them

by hand and the sheer bulk that such a volume would have.

So the Bible

is not 'a book' that man created, it is a collection of books

that was settled on as definitive over a long period. Some of the

details of which books belonged in that collection differed slightly

at differing times, which is why Catholic and Protestant Bibles

vary slightly in the (Old Testament) books they include.

It is not true

to say that the Bible 'evolved through countless translations'.

While the books of the Bible have been translated many times, the

modern text of the Old Testament is translated directly from the

original Hebrew, using the earliest available manuscripts, and the

modern text of the New Testament is translated directly from the

original Greek; again, from the earliest available manuscripts.

Brown's phrase 'evolved through countless translations' suggests

a 'Chinese whispers' transmission of information, with the insinuated

implication that original meanings may have been lost in these 'countless

translations'. While it is sometimes difficult to get to precisely

what the original Hebrew or Greek is saying, translations of the

Bible have always been directly from those original languages.

Back

to Chapters

The

Historical Jesus

"Jesus Christ was a historical figure of

staggering influence, perhaps the most enigmatic and inspirational

leader the world has ever seen. As the prophesied Messiah, Jesus

toppled kings, inspired millions, and founded new philosophies.

As a descendant of the lines of King Solomon and King David, Jesus

possessed a rightful claim to the throne of the King of the Jews.

Understandably, His life was recorded by thousands of followers

across the land."

(Chapter 55, p.231)

It is difficult

to know precisely what Teabing is saying in parts of this passage.

He seems to be talking about the historical figure of Jesus - the

preacher Yeshua bar Yosef who existed in the early First Century

AD and who Christians worship as 'Jesus Christ'. But the idea that

this wandering teacher and healer from Galilee 'toppled kings, inspired

millions and founded new philosophies' is quite fanciful. Despite

the gospels' claims of thousands of followers, he does not seem

to have attracted a very large following at all. He certainly did

not 'topple' any kings and his 'philosophy' may have been a radical

interpretation of Judaism, but he was a devout Jew not a founder

of 'new philosophies.

It could be,

however, that Teabing is talking about the figure that 'Jesus Christ'

became over the twenty centuries after his death.

His final sentence

is, however, completely incorrect. Jesus' life was not 'recorded

by thousands of followers across the land'. It seems no-one at all

recorded his career during his lifetime and that the first records

of his life were made from oral traditions, memories and folk stories

30-90 years after his death. There were only a handful of these

accounts and there is no evidence whatsoever that there were 'thousands'

of them.

"More than eighty gospels were considered

for the New Testament, and yet only a relative few were chosen for

inclusion--Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John among them.

(Chapter 55, p 231)

While there

were certainly more than just four gospels in circulation in the

first four centuries of the development of Christianity, the idea

that there were 'more than eighty gospels … considered for

the New Testament' is pure fantasy. We have copies of, references

to and fragments of about 18-20 gospels dating from the First to

the Third Centuries - the other 60 suggested by this statement of

Teabing's simply do not exist and there is no evidence for them

at all. Even taking into account various the 'Acts' and Epistles

(as opposed to 'gospels' per se) that were not included in the New

Testament, the count is still nowhere near 'eighty'.

Teabing is also

wrong when he says that Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were 'among'

the gospels which found their way into the final canon of the New

Testament - they were the only gospels included.

Back

to Chapters

Constantine,

Christianity and the New Testament

"Who chose which gospels to include?"

Sophie asked.

"Aha!" Teabing burst in with enthusiasm.

"The fundamental irony of Christianity! The Bible, as we know

it today, was collated by the pagan Roman emperor Constantine the

Great."

(Chapter 55, p. 231)

The long process

by which Christianity settled on the canon of the New Testament

- the books which were included in the Bible and regarded as definitive,

authoritative and divinely inspired - began long before the time

of Constantine the Great and continued for some time after he died.

Contrary to what Brown has Teabing declare here, Constantine was

not involved in this process in any way whatsoever.

The earliest

Christian communities of the First Century relied entirely on the

memories of Jesus' first followers. As these people died, an oral

tradition of stories and sayings of Jesus developed and began to

be written down in books. The four gospels which are now found in

the modern Bible - the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John -

were amongst these earliest collections of accounts of Jesus' life

and teaching. Other early writings also circulated amongst these

early communities, including the letters or 'Epistles' of Paul to

various early churches, letters by Peter and James and letters attributed

to them but probably written by other people. Some accounts of the

earliest followers, like the 'Acts of the Apostles', also came to

be used as sources of information, inspiration and authority by

these earliest communities.

But, at this

stage, there was no definitive list or 'canon' of these writings.

Any given isolated Christian community may well have known of some

of them but not others. They may also have had copies of a few of

them, but have only heard of others (since copies of any books were

expensive and precious). And they may also have used a variety of

other writings, many of which did not find their way into the Bible.

There was no single, central 'Church' which dictated these things

- each community operated in either relative isolation or intermittent

communication with other communities and there were no standardised

texts or a set list of which texts were authoritative and which

were not at this very early stage of the Christian faith.

Back

to Chapters

The

Beginnings of the Christian Canon

But the idea

of such a definitive list was not totally foreign to early Christianity.

Its parent religion, Judaism, had already wrestled with the problem

of a large number of texts all being claimed to be 'scriptural'

and inspired by God. Judaism generally agreed on the heart of its

canon: the Torah, also called the 'Pentateuch', or 'five scrolls'

because it was made up of the first five books of the Old Testament:

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. Judaism later

developed a wider canon called the 'Tanakh': twenty-four books,

including the five books of the Torah and adding the books of the

prophets, the Psalms and the historical books that can be found

in the Old Testament of Christian Bibles today.

Long before

Christians began to go through a similar process of determining

which texts were 'Scripture' and which were not, it is clear that

they already regarded some Christian texts as being on par with

those of the Jewish books of the Torah and the Tanakh. The Second

Letter of Peter was probably not written by Peter at all and was

most likely written in his name by someone around 120 AD; about

60 years or so after Peter died. But its author refers to certain

'false teachers' who misinterpret 'the letters of Paul' he says,

'just as they do with the rest of the Scriptures' (2 Peter 3:16).

So, as early as the beginning of the Second Century, the letters

of Paul were being regarded as 'Scripture', or divinely inspired

and authoritative works on the same level as the books of the Jewish

Bible.

As the Second

Century progressed there was more incentive for early Christianity

to define precisely which Christian texts were 'scriptural' and

which were not. In the Second Century a wide variety of new and

different forms of Christianity began to develop. The various Gnostic

sects were one prominent example, but it seems that it was the Marcionites

which gave the impetus for the first formulation of a Christian

canon of Scripture.

Back

to Chapters

Marcion

and his Canon

Marcion was

born around 100 AD in the city of Sinope on the southern coast of

the Black Sea. After a falling out with his father, the local bishop,

he traveled to Rome in around 139 AD. There he began to develop

his own Christian theology; one which was quite different to that

of his father and of the Christian community in Rome. Marcion was

struck by the strong distinction made by Paul between the Law of

the Jews and the gospel of Christ. For Marcion, this distinction

was absolute: the coming of Jesus made the whole of the Jewish Law

and Jewish Scriptures redundant and the 'God' of the Jews was actually

quite different to the God preached by Jesus. For Marcion, the Jewish

God was evil, vengeful, violent and judgmental, while the God of

Jesus was quite the opposite. Marcion decided that there were actually

two Gods - the evil one who had misled the Jews and the good one

revealed by Jesus.

This understanding

led Marcion to put together a canon of Christian Scripture - the

first of its kind - which excluded all of the Jewish Scriptures

which make up the Old Testament and which included ten of the Epistles

of Paul and only one of the gospels: the Gospel of Luke.

Marcion tried

to get his radical reassessment of Christianity and his canon accepted

by calling a council of the Christian community in Rome. Far from

accepting his teachings, the council excommunicated him and he left

Rome in disgust, returning to Asia Minor. There he met with far

more success, and Marcionite churches sprang up which embraced his

idea of two Gods and used his canon of eleven scriptural works.

Alarmed at his success, other Christian leaders began to preach

and write vigorously against Marcion's ideas and it seems that his

canon of eleven works inspired anti-Marcionite Christians to begin

to define which texts were and were not Scriptural.

Back

to Chapters

Early

Canon Lists

By around 180

AD the influence of Marcion, the growth of the various Gnostic sects

and the circulation of radical new 'gospels' began to be recognised

as a genuine threat to those Christians who considered these groups

fringe sects and heretical. It is around this time that we find

Irenaeus declaring that there are only four gospels which derive

from Jesus' earliest followers and which are Scriptural. These are

the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John: the ones found in the

Christian Bible today. Irenaeus makes it clear that these four had

always been regarded as the earliest and most authoritative and

were therefore the ones to be trusted as true accounts of Jesus'

life, works and teachings. Interestingly, after two centuries of

sceptical analysis, the overwhelming majority of historians, scholars

and textual experts (Christian or otherwise) actually agree with

Irenaeus and the consensus is that these four gospels definitely

are the earliest of the accounts of Jesus' life.

Not long after

Irenaeus' defence of the four canonical gospels we get our first

evidence of a defined list of which texts are scriptural. A manuscript

called the Muratorian Canon dates to sometime in the late Second

Century AD and was discovered in a library in Milan in the Eighteenth

Century. It details that the canonical four gospels - Matthew, Mark,

Luke and John - along with most of the other books found in the

modern New Testament, as well as a couple which are not (the Wisdom

of Solomon and the Apocalypse of Peter) are 'scriptural' and authorative.

It also gives some approval to other, more recent works like The

Shepherd of Hermas, but says they should not be read in church as

scripture.

The Muratorian

Canon document accepts twenty-three of the twenty-seven works which

now make up the New Testament in the Bible. It also explicitly rejects

several books on the grounds that they are recent and written by

fringe, heretical groups and it specifically singles out works by

the Gnostic leader Valentius and by Marcion and his followers.

It seems that

the challenge posed by Marcion and other dissident groups caused

the early Christians to determine which books were scriptural and

which were not. And it also seems that recent works, whether they

were 'heretical' (like the Gnostic gospels) or not (like The Shepherd

of Hermas), did not have the status of works from the earliest years

of Christianity. It was only these earliest works which were considered

authoritative.

Back

to Chapters

The

Final Formation of the Christian Canon

It is clear

that the process of deciding which texts were canonical and which

were not was already well under way over a century before the Emperor

Constantine was even born. It also continued for a long time after

he died. Constantine's contemporary, the Christian historian Eusebius,

set out to 'summarise the writings of the New Testament' in his

Church History; a work written towards the end of Constantine's

reign. He lists the works which are generally 'acknowledged' (Church

History, 3.25.1), including the four canonical gospels, Acts,

the Epistles of Paul, 1 John, 1 Peter and the Apocalypse of John/'Revelation'

(though he says this is still disputed by some). He gives other

texts which he says are 'still disputed'; including James, Jude,

2 Peter and 2 and 3 John. He gives other books which are probably

'spurious' and then lists others which are definitely considered

heretical, including the Gospels of Peter, Thomas and Matthias and

the Acts of Andrew and John.

So not only did the process of deciding the canon begin long before

Constantine, there was still debate within the Church about the

canon in his time.

And it continued.

In 367 Athanasius wrote his 39th

Festal Letter in which he laid out the current twenty-seven

books of the New Testament - the first time this canon had been

definitively stated by any churchman. A synod convened in Rome by

Pope Damasus in 382 AD also considered the question of the canon

and, with the help of the great scholar Jerome, settled on the same

twenty-seven books set out by Athanasius. At this stage there was

still no central authority which could compel church communities

in any way (despite Dan Brown's frequent anachronistic references

to a central 'Vatican'), but councils and synods in Hippo and Carthage

in north Africa and later ones in Gaul also settled on the same

canon.

Despite Brown's totally erroneous claim that the canon was determined

by Constantine in 325 AD, there was actually no definitive statement

by the Catholic Church as to the make-up of the New Testament until

the Council of Trent in 1546: a full 1209 years after Constantine

died. The full development of the canon took several centuries,

but the basics of which gospels were to be included was settled

by 200 AD at least.

And Constantine had absolutely nothing to do with any of this process.

This claim by Dan Brown is completely incorrect in every way.

Back

to Chapters

The Conversion of Constantine

"I thought Constantine was a Christian,"

Sophie said.

"Hardly," Teabing scoffed. "He

was a lifelong pagan who was baptized on

his deathbed, too weak to protest."

(Chapter 55, p. 232)

Constantine

lived most of his life as a worshipper of Sol Invictus - a state-approved

Roman sun-god cult closely aligned with the originally Persian cult

of Mithras, but which was originally quite separate from it. Mithras

had long been a popular cult amongst Roman soldiers, since it was

exclusively male, highly selective about whom it admitted and involved

at least seven secretive levels of initiation.

Constantine's

family, however, included several Christians, notably his mother

Helena and his sister. Teabing's scoffing suggestion that Constantine

was baptised against his will 'too weak to protest' ignores Constantine's

obvious alignment with Christianity long before his death; from

his victory at the Milvian Bridge onwards. Deathbed baptisms were

actually very common at this time and there is absolutely nothing

to suggest that it was somehow against the Emperor's will or that

he wanted to 'protest'. Evidence about Constantine's beliefs are

confused, probably because he himself was fairly unclear about which

God or gods he worshipped. As a soldier and politician, he was quite

unsophisticated about religion and probably considered Jesus, God,

Sol Invictus and, perhaps, Mithras to be all the same being. His

mind was on more earthly concerns.

Back

to Chapters

The

Conversion of the Roman Empire

In Constantine's day, Rome's official religion

was sun worship--the cult of Sol Invictus, or the Invincible Sun

- and Constantine was its head priest. Unfortunately for him, a

growing religious turmoil was gripping Rome. Three centuries after

the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, Christ's followers had multiplied

exponentially. Christians and pagans began warring, and the conflict

grew to such proportions that it threatened to rend Rome in two.

Constantine decided something had to be done. In 325 A.D., he decided

to unify Rome under a single religion. Christianity."

(Chapter 55, p. 232)

There are several

blatant historical mistakes in this passage. In Constantine's time

Rome's official state religion was still the worship of the old

Roman gods, headed by Jupiter Optimus et Maximus ('Jupiter Best

and Greatest'). The cult of Sol Invictus, which was closely aligned

with but not identical to the originally Persian cult of Mithras,

was certainly popular, especially in the army. Constantine seems

to have been a worshipper of Sol Invictus - the Unconquered Sun

- and probably also of Mithras, though whether he was an initiate

of Mithras' seven levels of 'mysteries' is unknown. He depicted

the god Sol Invictus on his coins, with the inscription 'SOLI INVICTO

COMITI', and he declared 'Dies Solis' (Sunday) as a day of rest.

It is certainly

true that in the three centuries leading up to Constantine's reign

Christianity had been growing in popularity. Unlike many of its

rival religions, like Mithraism, Christianity was completely non-exclusive,

being open to anyone, including women and slaves. Official cults,

like the old Roman religion and the cult of Sol Invictus, were hierarchical

and heavily politicised. And 'mystery cults', like Mithraism and

the cult of Cybele, were exclusive clubs open by invitation only.

Christianity, on the other hand, was open to all. Its creed, with

its emphasis on equality, justice and regard for the poor and oppressed,

made it popular, as did the social and economic support networks

it offered in the form of charity for the poor.

That said, Christians

were by no means the majority in the Empire when Constantine came

to the throne. It is estimated that they formed no more than 5-10%

of the total population. Despite this, there were Christians in

positions of influence, including in the Imperial family: Constantine's

mother Helena was probably born a Christian, was famously devout

and had a definite influence on her son.

But it is not

true that 'pagans and Christians began warring' or that this supposed

conflict 'threatened to 'rend Rome in two'. There was conflict between

pagans and Christians before Constantine's accession, but it was

almost entirely one sided: pagan Emperors persecuting Christians.

Christians had been persecuted on and off since the earliest days

of their religion. As a misunderstood minority group, and one with

Jewish origins, they were often scapegoated when things went wrong.

As Tertullian wrote:

'If the Tiber

reaches the walls, if the Nile fails to rise to the fields, if the

sky doesn't move or the earth does, if there is famine or plague,

the cry is at once: "The Christians to the lions!"'

The other reason

for the persecutions was that religion in the Roman Empire was intimately

linked to the state. All cults, official or not, were supposed to

offer prayers and sacrifices for the good of the Emperor and his

regime. Some 'legal religions' - such as Judaism - were exempt,

but 'cults' like Christianity were not. Christians, however, found

sacrifices on behalf of or even to the Emperors totally unacceptable,

and this was considered not just treasonous, but actually dangerous

to the well-being of the Empire.

The persecutions

came to a climax in the reign of Diocletian, though it was his eastern

sub-Emperor Gallenius who made them particularly systematic and

savage. Christians were forced to sacrifice to show their loyalty

to the state and those that refused were imprisoned, tortured and,

in many cases, savagely executed. Many others were exiled and church

property was confiscated in a campaign of persecution which went

on for nearly ten years.

Constantine

brought this to an end when he became Emperor. In 313 AD he passed

the 'Edict of Milan' which ordered the tolerance of all religions

in the Empire, commanded the end of the persecution of Christianity

and the return of confiscated church property.

This ended the

persecutions, but it definitely did not 'unify Rome under a single

religion'. Christianity certainly gained favour and benefits after

313 AD, but Constantine did not make it the official state religion

- that did not happen until the reign of Theodosius, in 381 AD.

Sophie was surprised. "Why would a

pagan emperor choose Christianity as the official religion?"

Teabing chuckled. "Constantine was a very good businessman.

He could see that Christianity was on the rise, and he simply backed

the winning horse. Historians still marvel at the brilliance with

which Constantine converted the sun-worshipping pagans to Christianity.

By fusing pagan symbols, dates, and rituals into the growing Christian

tradition, he created a kind of hybrid religion that was acceptable

to both parties."

(Chapter 55, p. 232)

We know that

Constantine did not make Christianity 'the official religion'; he

simply ended its official persecution. And it is also wrong to depict

Christianity in this period as 'the winning horse', since Christians

still formed a minority in the Empire. We know that Constantine

had been personally attracted to Christianity for some time. Eusebius

tells the story of how he had a vision of Jesus before the key battle

for supremacy against his Imperial rival at the Milvian Bridge and

his troops carried shields with the Christian 'Chi-Ro' symbol long

before the Edict of Milan in 313 AD.

That said, it

is hard to say precisely how Christian the Emperor was. He seems

to have been an immensely superstitious man and probably shared

the view of many Roman soldiers that it was unwise to anger any

gods, lest they turn against you in battle. Constantine was a soldier,

a politician and an administrator, not a devout believer or a theologian.

To him, the sun-god, Sol Invictus, and the Christian God were probably

the same being, so the adjustment from being a pagan with Christian

sympathies to a Christian with some pagan attitudes would not have

been a large one. He proved to be a ruthless and sometimes savagely

cruel ruler, ordering massacres and executing several of his own

family, so it would be wrong to see him as some pious and holy convert.

Long after he made his attraction to Christianity clear, he still

raised a statue of Sol Invictus in his new capital of Constantinople

and, in a typically egomaniacal gesture, gave it his own facial

features.

Teabing's depiction

of his adoption of Christianity and his sponsoring of that religion

after 313 AD as a purely cynical, political and totally artificial

affair is a distortion of a much more complex picture. Constantine's

Christianity, such as it was, seems to have been entirely sincere,

if slightly unsophisticated or even rather confused. There is no

evidence he deliberately set out to create a cynical synthesis of

paganism and Christianity for his own ends. Any fusing of 'symbols,

dates and rituals' from the two religious traditions had been happening

for some time already. If Constantine's toleration of and sponsorship

of Christianity added to this, it was accidental, not cynically

deliberate.

Back

to Chapters

Christianity

and Pagan Borrowings

"Transmogrification," Langdon said.

"The vestiges of pagan religion in Christian symbology are

undeniable. Egyptian sun disks became the halos of Catholic saints.

Pictograms of Isis nursing her miraculously conceived son Horus

became the blueprint for our modern images of the Virgin Mary nursing

Baby Jesus."

(Chapter 55, p. 232)

It is certainly

undeniable that some aspects of Christian iconography (there is

no such thing as 'symbology') were derived from pre-Christian art.

The halos found in Christian depictions of saints are most likely

to be derived from Roman depictions of Emperors with a 'nimbus'

around their heads, which was in turn derived from Greek depictions

of gods and demi-gods with a similar radiance. It is actually unlikely

that much earlier 'Egyptian sun disks' had anything to do with any

of these artistic conventions. These traditions were far from the

only ones which associated radiance of the face and head with holiness.

Christianity had its own tradition of this - Matthew 17:2 describes

the 'Transfiguration' of Jesus where, it is said, his 'face shone

like the sun'. Jewish tradition had a similar story of Moses, whose

face was said to have radiated light after he came down from Mount

Sinai (Exodus 34: 29-35). So while it is likely the Christian artistic

convention of the halo came from Greek and Roman conventions, it

was also in keeping with a long standing Christian and Jewish association

of holiness with a shining face and head.

It is also true

that depictions of Isis and the child Horus probably did influence

the later depictions of Mary and the baby Jesus. What is totally

unlikely, however, is Langdon's implication that these borrowings

and influences were part of some deliberate attempt (by Constantine,

apparently) to fuse Christianity with paganism. This is pure fantasy.

"And virtually all the elements of the Catholic

ritual - the miter, the altar, the doxology, and communion, the

act of "God-eating"-were taken directly from earlier pagan

mystery religions."

(Chapter 55, p.232)

This statement

is completely incorrect. The mitre (or 'miter', to use Brown's American

spelling) was not used in the Western (ie Catholic) Church until

the Tenth Century and so could not have had anything to do with

pagan mystery cults which had died out over 600 years previously.

Altars have been a part of many religions, but the altars in Christian

churches owe more to the altars of Christianity's progenitor faith,

Judaism, than any pagan practice. There are over 300 references

to altars in the Jewish scriptures and many important references

to altars in the Christian New Testament, including no less than

six references to a heavenly altar before the throne of God himself

(Revelation 6:9; 8:43; 9:13; 11:1; 14:8 and 16:7)

A 'doxology'

is a hymn of praise, though Brown here seems to be referring to

the 'Great Doxology' which forms part of the Catholic mass liturgy.

But this prayer is made up, like most Catholic liturgy, of phrases

from the Old and New Testaments and was not derived from any known

pagan prayers at all.

The same goes

for the reference in The Da Vinci Code passage above to 'the

act of "God eating"'. Several pagan mystery cults, including

Mithraism, included a communal meal, often of bread and wine. This

is unsurprising, as bread and wine were staple foods in the Roman

period. None of these cult meals, however, had any association with

'God eating' and bore no resemblance to the beliefs surrounding

the Christian meal of bread and wine regarding Jesus' body and blood.

Paul refers to this sacred meal as early as 50 AD (1 Corinthians

11:23-25) and makes it clear that it derived from the meal Jesus

shared with his followers before his arrest. Any similarity with

the cult meals of the pagan mystery religions is purely co-incidental.

Interestingly,

this passage in The Da Vinci Code is actually taken directly,

almost word for word, from an evangelical Protestant pamphlet attacking

the Catholic Church, associating it with pagan practices and arguing

that, as such, Catholicism is not truly Christian. 'Bible Prophecy

for the World Today', in a pamphlet reproduced on the Web, describes

Catholicism in this way:

'Constantine

converted sun worshipping pagans to Christianity by fusing pagan

symbols, rituals and dates into a hybrid religion. The marks

or symbols from pagan religion in Christianity today are undeniable.

Egyptian sun disks became the halos of Catholic saints, pictograms

of Isis nursing her reborn son, Horus, became a symbol of modern

images of Mary nursing baby Jesus. Nearly all the elements of the

Roman Catholic rituals, the miter, doxology, the alter, and communion

were taken directly from earlier pagan religions.'

('Bible

Prophecy for the World Today - 'Constantines (sic) Destruction

of Christanity (sic)')

The section

in bold from this pamphlet is actually almost word for word what

Brown puts in the mouth of Langdon in The Da Vinci Code. Brown clearly

cut and pasted this passage, unchanged, from this online religious

pamphlet. This anti-Catholic document, in turn, takes its information

from Alexander Hislop's The

Two Babylons: Or The Papal Worship Proved to be the Worship of Nimrod

and His Wife, first published back in 1858. Hislop was a

fanatical anti-Catholic who set out to 'prove' that Catholicism

was simply paganism in disguise.

His book was,

and continues to be, very influential in some highly conservative,

anti-Catholic, fundamentalist Protestant circles and it heavily

influenced a young evangelical preacher called Ralph Woodrow, who

used it as the basis for his own book Babylon Mystery Religion.

When a history teacher challenged Woodrow on the accuracy of his

research and called Hislop's scholarship into question, Woodrow

set about checking the accuracy of Hislop's research. He found it

was completely fraudulent, riddled with misquotations and misrepresentations

and totally lacking in any historical integrity. To his credit,

Woodrow promptly withdrew his own book from publication, wrote another

book exposing Hislop's many errors and became a strident critic

of Hislop's ideas. He wrote:

'[The Two

Babylons] claims that the very religion of ancient Babylon, under

the leadership of Nimrod and his wife, was later disguised with

Christian-sounding names, becoming the Roman Catholic Church. Thus,

two "Babylons"-one ancient and one modern. Proof for this

is sought by citing numerous similarities in paganism. The problem

with this method is this: in many cases there is no connection.'

(Ralph Woodrow,

'The Two Babylons:

A Case Study in Poor Methodology')

So Langdon's

statement here is lifted by Brown directly from an online fundamentalist

Christian pamphlet, which in turn is basing its information on a

Nineteenth Century piece of anti-Catholic polemic which has not

only been discredited by historians, but has been rejected by other

Protestant evangelicals.

Teabing groaned. "Don't get a symbologist

started on Christian icons.

Nothing in Christianity is original. The pre-Christian God Mithras-called

the Son of God and the Light of the World--was born on December

25, died, was buried in a rock tomb, and then resurrected in three

days. By the way, December 25 is also the birthday of Osiris, Adonis,

and Dionysus. The newborn Krishna was presented with gold, frankincense,

and myrrh.

(Chapter 55, p. 232)

Everything in

this set of assertions by Teabing seems to be based on Kersey Graves,

The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors, published in 1875.

Graves was writing with a clear anti-Christian agenda and while

his book remains popular in certain circles, it has been comprehensively

rejected by historians as an amateurish pastiche of fantasy and

misinterpreted evidence. Graves rarely actually gives any sources

or supporting evidence for his assertions about the pagan roots

of Christianity and it is regarded by scholars, whether Christian

or otherwise, as an inventive but baseless piece of junk pseudo-scholarship

of no value.

For example,

the atheist web-site 'Secular Web' includes a

link to an online edition of Graves' book but prefaces it

with the following warning:

'Note: the

scholarship of Kersey Graves has been questioned by numerous theists

and nontheists alike; the inclusion of his The World's Sixteen Crucified

Saviors in the Secular Web's Historical Library does not constitute

endorsement by Internet Infidels, Inc. This document was included

for historical purposes; readers should be extremely cautious in

trusting anything in this book.'

Given the lack

of credibility of this source, it is not surprising that the statements

that Teabing makes above do not stand up to even the slightest scrutiny.

For example,

no-where in any of the material we have regarding Mithras is he

called 'the Son of God' or 'the Light of the World' - this comes

from Graves' imagination. Similarly, the idea that Mithras, Osiris,

Adonis, and Dionysus all had 'birthdays' on December 25th is pure

fantasy. Most of these deities were regarded as eternal beings who

had no 'birthday' at all and the others had no dedicated day of

birth. All this, once again, comes from Graves, probably via Holy

Blood, Holy Grail and The Templar Revelation, as Brown gets most

of his 'information' second hand from dubious, unscholarly sources.

The Roman solar

cult of Sol Invictus, however, did have December 25th as the central

feast day of the sun god. Since this cult and the cult of Mithras

were closely aligned, it may be that Roman Mithraism also held this

day in high regard. Christian tradition did not record on what day

Jesus was born, so it certainly seems be true that Christianity

took December 25th as the day on which Jesus' birth should be celebrated

largely because of its association with the holy day of the Sol

Invictus cult. In other words, just as Mithraism took December 25th

from the Sol Invictus cult, so Christianity took it from Mithraism.

That is how ancient religion tended to work.

There are other

possibilities, however. There was a belief in Judaism that great

prophets died on the date of their birth or of their conception.

Most Christians believed that Jesus was conceived on March 25th,

so it could have been argued, then, that he was born on December

25th.

That aside,

according to Roman-era Mithraism, Mithras was born fully formed

out of a rock. There are, despite Teabing's assertions, no legends

about Mithras dying, being buried in a rock tomb or rising again.

This is pure fantasy with no foundation whatsoever.

Teabing's statement

that 'The newborn Krishna was presented with gold, frankincense,

and myrrh' is also taken directly from Graves and is, like most

of his assertions, supported by no evidence at all. The First Century

Hindu scripture, Bhagavad-Gita, makes no mention of Krishna's

birth or childhood at all. The first mentions of his childhood come

in the Harivamsa Purana (circa 300 AD) and the Bhagavata

Purana (circa 800-900 AD), neither of which mention any gifts

for the baby Krishna, let alone 'gold, frankincense and myrrh'.

Once again, this claim is completely baseless.

Even Christianity's weekly holy day was stolen

from the pagans."

"What do you mean?"

"Originally," Langdon said, "Christianity honored

the Jewish Sabbath of

Saturday, but Constantine shifted it to coincide with the pagan's

veneration day of the sun." He paused, grinning. "To this

day, most churchgoers attend services on Sunday morning with no

idea that they are there on account of the pagan sun god's weekly

tribute--Sunday."

(Chapter 55, pp. 232-233)

The historical

evidence clearly indicates that this claim is totally incorrect.

Christians were worshipping on Sunday rather then the Jewish Sabbath

of Saturday long before Constantine was even born. The practice

of gathering for worship on Sunday is referred to in 1 Corinthians

16:2 (dated to 50-60 AD) and Acts 20:7 (circa 80-100 AD). Sunday

was called Dies Domini or 'the day of the Lord' and is mentioned

as the day for Christian worship by Ignatius of Antioch around 110

AD, who specifically states 'we no longer observe the Jewish Sabbaths,

but keep holy the Lord's day.'(Epistle to the Magnesians,

Ch. 9). This practice of worshipping on 'the Lord's day' rather

than Saturday is also mentioned in The Epistle of Barnabus

(circa 90 AD), the Didache (50-110 AD) and by Justin Martyr

(circa 150 AD).

Tertullian,

writing around 200 AD, talked of Sunday being a day of rest as well

as worship, and this was also stated by the local church Council

of Elvira in Spain in 303 AD. What Brown seems to be basing his

assertions in this passage on is an edict by Constantine in 321

AD which made Sunday an official day of rest for all citizens of

the Empire. But his statements in this passage make it sound as

though Christians worshipped on Saturday up to this point and only

changed at Constantine's (pagan) insistence. This is completely

incorrect.

As is his statement

that modern church-goers attend worship on 'Sunday' unaware that

the change was made by Constantine to put a veneer of Christianity

over a day of pagan sun-worship. Not only was the change not made

by Constantine, but Christians actually worshipped on Sundays despite

that day's association with sun-worship. They chose that day because

that was the day they believed Jesus rose from the dead. As Jerome

wrote in the early Fifth Century:

The Lord's Day,

the day of Resurrection, is our day. It is called the Lord's day

because on it the Lord rose victorious to the Father. If pagans

call it the 'day of the sun', we willingly agree, for today the

light of the world is raised, today is revealed the sun of justice

with healing in his rays.

(Paschal Sermons, CCL 78, 550)

Constantine

did not change the Christian day of worship from Saturday to Sunday;

that had happened at least 200 years before he was even born. And

the reason for the change was that Sunday was the day Christians

believed Jesus rose from the dead; it had nothing to do with it

being the 'day of the Sun'.

Back

to Chapters

Jesus made into a God?

Sophie's head was spinning. "And all of

this relates to the Grail?"

"Indeed," Teabing said. "Stay

with me. During this fusion of religions, Constantine needed to

strengthen the new Christian tradition, and held a famous ecumenical

gathering known as the Council of Nicaea."

Sophie had heard of it only insofar as its being

the birthplace of the Nicene Creed.

"At this gathering," Teabing said,

"many aspects of Christianity were debated and voted upon--the

date of Easter, the role of the bishops, the administration of sacraments,

and, of course, the divinity of Jesus."

"I don't follow. His divinity?"

"My dear," Teabing declared, "until

that moment in history, Jesus was viewed by His followers as a mortal

prophet... a great and powerful man, but a man nonetheless. A mortal."

"Not the Son of God?"

"Right," Teabing said. "Jesus'

establishment as 'the Son of God' was officially proposed and voted

on by the Council of Nicaea."

(Chapter 55, p. 233)

Of all the assertions

made by the characters in The Da Vinci Code, this is probably

one of the ones which has caused the most real controversy. Many

of the statements that Brown claims or insinuates are credible are

dubious at best, but this one is particularly contentious. Christians,

naturally, object to the idea that their Messiah was considered

as simply a mortal prior to the Council of Nicea in 325 AD, since

they regard him as God in human form. But non-Christian historians

also find this particular assertion totally objectionable to the

point of being laughable, since it flies in the face of a vast body

of historical evidence.

Put simply,

what Brown has Teabing state here is completely and categorically

wrong in every way.

While Christians

reject the idea that Jesus was 'turned into a God' at any point

as a matter of faith, non-Christian historians accept that 'Jesus'

was a First Century Jewish preacher and healer who later became

regarded as, somehow, God in human form. Where they differ from

what Brown is implying through Teabing is when and how

this occurred.

According to

Brown, via Teabing and Langdon, this transition happened abruptly

in 325 AD, when (by their account) the pagan Emperor Constantine

co-opted Christianity for his own political ends and imposed various

pagan elements on it which did not exist before. The most important

of these, according to Brown's narrative, was turning Jesus from

a mortal prophet into a God-Man. As Brown tells it, "until

that moment in history, Jesus was viewed by His followers as a mortal

prophet... a great and powerful man, but a man nonetheless. A mortal."

This is contrary

to the evidence in every possible respect.

We have no shortage

of writings from Christians of the Second, Third and Fourth Centuries

AD and they regularly tell of their perception of who and what Jesus

was. If Teabing, Langdon (and Brown) are correct, we should see

a sharp break around 325 AD, with earlier writers referring to Jesus

only as a mortal prophet and later ones adopting this 'pagan' idea

of him being a god in human form. But we do not see this at all.

The evidence

from all Christian writings prior to 325 AD, right back to the late

First Century and within a generation or two of Jesus' own time,

indicates clearly that the overwhelming majority of Christians regarded

Jesus as God long before 325 AD, before the Council of Nicea and

centuries before Constantine was even born. Non-Christian historians

agree that the process of turning the mortal Jewish preacher, Yeshua

bar Yosef, into the divine being 'Jesus Christ' was well underway

as early as 90 AD and was more or less complete by the middle of

the Second Century.

A sample of

the writings about the nature of Jesus from Christians from the

late First Century to Constantine's time shows exactly how totally

ridiculously wrong The Da Vinci Code's claims are in this

respect:

Ignatius

of Antioch (50 AD-117 AD)

"Ignatius

... to the Church which is at Ephesus, ... united and elected through

the true passion by the will of the Father, and Jesus Christ, our

God."

(Letter to the Ephesians, Prologue)

"There

is one physician who is possessed of both flesh and spirit; both

made and not made; God existing in the flesh; true life in death;

both of Mary and of God; first possible and then impossible, even

Jesus Christ our Lord."

(Letter to the Ephesians, Chapter 7)

"Do everything

as if he (Jesus) were dwelling in us. Thus we shall actually be

his temples and he will be within us as our God - as he actually

is .... For our God, Jesus Christ .... was born and baptised, that

by his passion he might purify the water."

(Letter to the Ephesians, Chapter 15)

"Jesus

Christ, who was with the Father before the beginning of time"

(Letter to the Magnesians, Chapter 6)

"...I pray

for your happiness for ever in our God, Jesus Christ, ..."

(Letter to Polycarp, Chapter 8)

" "Ignatius,

who is also called Theophorus, to the Church which has obtained

mercy, through the majesty of the Most High Father, and Jesus Christ,

His only-begotten Son; the Church which is beloved and enlightened

by the will of Him that willeth all things which are according to

the love of Jesus Christ our God, which ... is named from Christ,

and from the Father, which I also salute in the name of Jesus Christ,

the Son of the Father: to those who are united, both according to

the flesh and spirit, to every one of His commandments; who are

filled inseparably with the grace of God, and are purified from

every strange taint, [I wish] abundance of happiness unblameably,

in Jesus Christ our God."

(Letter to the Romans, Prologue)

Aristides

(123-4 or 129AD)

(Aristides was

a non-Christian philosopher from Athens. In a letter to the Emperor

Hadrian he describes what various religions believe about God and

the gods):

"The Christians,

then, trace the beginning of their religion from Jesus the Messiah;

and he is named the Son of God Most High. And it is said that God

came down from heaven, and from a Hebrew virgin assumed and clothed

himself with flesh; and the Son of God lived in a daughter of man.

This is taught in the gospel, as it is called, which a short time

was preached among them; and you also if you will read therein,

may perceive the power which belongs to it. This Jesus, then, was

born of the race of the Hebrews; and he had twelve disciples in

order that the purpose of his incarnation might in time be accomplished."

(Letter to Hadrian, Chapter 2)

Polycarp

(110-130 AD)

"...to

all under heaven who shall believe in our Lord and God Jesus Christ

and in his Father who raised him from the dead."

(Letter to the Phillipians, Chapter 12)

" 'For

whosoever does not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh,

is antichrist;' and whosoever does not confess the testimony of

the cross, is of the devil."

(Letter to the Phillipians, Chapter 7)

Justin Martyr

(165 AD)

"The Father

of the universe has a Son; who also, being the first-begotten Word

of God, is also God."

(First Apology, Chapter 63)

"...which

I wish to do in order to prove that Christ is called both God and

Lord of hosts..."

(Dialogue with Trypho, Chapter 36)

"And there

are some who maintain that even Jesus Himself appeared only as spiritual,

and not in flesh, but presented merely the appearance of flesh:

these persons seek to rob the flesh of the promise."

(Dialogue with Trypho, Chapter 2)

"For if

you had understood what was written by the prophets, you would not

have denied that he (Jesus) was God, Son of the only, unbegotten,

unutterable God."

(Dialogue with Trypho, Chapter 126)

Melitio of

Sardis (170 AD)

"Born

as a son, led forth as a lamb, sacrificed as a sheep, buried as

a man, he rose from the dead as a God, for he was by nature God

and man. He is all things: he judges, and so he is Law; he teaches,

and so he is Wisdom; he saves, and so he is Grace; he begets, and

so he is Father; he is begotten, and so he is Son; he suffers, and

so he is Sacrifice; he is buried, and so he is man; he rises again,

and so he is God. This is Jesus Christ, to whom belongs glory for

all ages."

(Apology, 8-10)

"Being

God and likewise perfect man, he (Jesus) gave positive indications

of his two natures: of his deity ... and of his humanity ..."

(Apology, 13)

Clement of

Alexandria (150-215 AD)

"He (Jesus)

alone is both God and man, and the source of all our good things."

(Exhortation to the Greeks, 1:7:1)

"(Jesus

is) the expiator, the Saviour, the soother ... quite evidently true

God."

(Exhortation to the Greeks, 1:7:1)

Tertullian

(193 AD)

"God alone

is without sin. The only man who is without sin is Christ, for Christ

is also God."

(The Flesh of Christ, 41:3)

"The origins

of both his substances display him as man and as God."

(The Flesh of Christ, 5:6-7)

Origen (225

AD)

"Although

(Jesus the Son) was God, he took flesh; and having been made man,

he remained what he was: God."

(The Fundamental Doctrines, I, Preface, 4)

It is perfectly

clear from these and many other such quotes from the first three

centuries of Christianity that the idea that Jesus was God had been

well established over 200 years before the Council of Nicea. The

idea that it began then, in 325 AD, contradicts masses of evidence

about what Christians believed in this period.

This is one

of the most fundamental errors of fact made in the whole of The

Da Vinci Code and it is one of the reasons why historians, non-Christian

and Christian, regard the novel's historical claims as utterly ridiculous.

The

Council of Nicea

"Hold on. You're saying Jesus' divinity

was the result of a vote?"

"A relatively close vote at that," Teabing added.

(Chapter 55, p. 233)

There certainly

was a vote at the Council of Nicea, but it was not (contrary to

Teabing's claims) on whether Jesus was God. When Constantine became

Emperor in 312, he attributed his victory at the Battle of the Milvian

Bridge to a vision he saw of Jesus Christ before the battle. While

not a Christian himself, he was heavily influenced by his devoutly

Christian mother and sister and, like many superstitious soldiers,

he was not keen to antagonise a god. But he was also a canny politician

and he saw that decades of oppression and persecution had failed

to suppress Christianity. Christians still formed a minority in

the Empire's population, but it was a sizeable and active minority,

so in 313 AD Constantine passed the Edict of Milan which ended the

persecution of Christianity and made the religion entirely legal

and legitimate. Constantine saw the political benefit of working

with Christianity and harnessing it to assist his goal of uniting

his fractured Empire. He did not, as is often claimed, make Christianity

the 'official religion of the Empire' however: that happened at

the end of the Fourth Century under the Emperor Theodosius in 381

AD.

After the passing

of the Edict of Milan Constantine quickly realised that Christianity

itself was far from united. The faith was torn by internal doctrinal

and theological disputes which, with the end of state persecution,

now came to the fore. The most divisive of these was the 'Arian

Dispute' - a heated debate within the churches over the nature of

Jesus' divinity.

Christians by

this stage all agreed that Jesus was both God and Man, but there

was a bitter dispute raging about how he could be both and

how he, as God, stood in relation to the first person of the Trinity,

God the Father. Saint Alexander of Alexandria led the majority faction

that believed Jesus was both fully God and Man and was 'of one substance

with the Father', being entirely equal to him in every way. He was

opposed by the popular and eloquent presbyter Arius, who maintained

that Jesus was both God and Man, but argued that Jesus 'proceeded

from the Father' and so was, in a sense, lesser than or subordinate

to him.

To Constantine,

this tiny theological difference was 'trifling' and he was frustrated

by the way this seemingly small difference in semantics was causing

bitter disputes and dissent within Christianity. His rule was based

on an often ruthless policy of 'unity at all costs' - coming as

it did after a period of bitter divisions and bloddy civil war.

He also prided himself on his ability to conciliate between disputing

parties and create a consensus so, in 325 AD, he called all the

bishops of the Empire to a council at his lakeside palace in Nicea

(now Iznik in modern Turkey) to settle the problem once and for

all.

Somewhere between

250 and 318 bishops attended, accompanied by hundreds of attendants.

Constantine opened the proceedings but, being easily bored by theological

debate, rapidly lost interest in the days of complex theological

dispute and actually played little role in the proceedings of the

Council itself. In the end, Alexander won the day and, in the final

vote on the question of Jesus' divine substance, only two bishops

of the 250 voted in favour of Arius.

So the Council

of Nicea was not called to vote on 'whether Jesus was God', but

on how, as God, he stood in relation to God the Father. And there

was no 'relatively close vote' either - 99% of the bishops voted

against Arius. Yet again, Brown completely misrepresents history.

Back

to Chapters

The

Vatican

"Nonetheless, establishing Christ's divinity

was critical to the further unification of the Roman empire and

to the new Vatican power base. By officially endorsing Jesus as

the Son of God, Constantine turned Jesus into a deity who existed

beyond the scope of the human world, an entity whose power was unchallengeable.

This not only precluded further pagan challenges to Christianity,

but now the followers of Christ were able to redeem themselves only

via the established sacred channel-the Roman Catholic Church."

Sophie glanced at Langdon, and he gave her a

soft nod of concurrence.

(Chapter 55, p.233)

Clearly part

of Constantine's motives was political and he certainly did see

the advantages of having a united Christianity as a political ally.

But, as can be seen above, the Council did not invent the

idea of Jesus as God and that was not what was discussed there and

voted on.

This is also

one of the passages where Brown makes anachronistic use of the word

'Vatican'. Throughout the novel he uses 'the Vatican' to mean the

Catholic Church, but it actually makes no sense to refer to any

'Roman Catholic Church' in the Fourth Century or to refer to such

a Church as 'the Vatican'. In Constantine's time there actually

was no single 'Church' at all, let alone one that was 'Roman'. Christianity,

at this time, consisted of a loose collection of church communities,

each headed by their bishop, archbishop or patriarch and, as the

dispute which led to the Council of Nicea shows, these communities

were far from united. The Bishop of Rome, whose successors were

to become the popes of later centuries, claimed a certain authority

as successors of Saint Peter, but he was seen as no more prestigious

in rank as the other great patriarchs: the bishops of Jerusalem,

Antioch, Alexandria and Constantinople. It was only centuries later,

when Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem had fallen to the Muslims

and Constantinople and Rome separated over doctrine, that the Popes

began to claim 'primacy' over other bishops. To talk about a 'Roman

Catholic Church' in the Fourth Century is ridiculous.

As is using

the word 'Vatican'. In the Fourth Century the Vatican was simply

a hill in Rome; one dominated mainly by a small church and an overgrown

graveyard. The Bishops of Rome came to live in the Lateran Palace

- a gift from the Emperor - until the Fourteenth Century when the

Papacy fled Rome for the French city of Avignon. On returning to

Rome in 1378 the papal administration became established on the

Vatican Hill, but the Pope lived on the Quirinal Hill. The Vatican

only became the home of the Pope in 1871.

The term 'the

Vatican' is often used as a shorthand for the modern government

of the Catholic Church and the Papacy in general. But talking about

'the Vatican' doing anything in the Fourth Century is rather like

talking about US Congress establishing Jamestown in the Sixteenth

Century. It is anachronistic to the point of being totally nonsensical.

Back

to Chapters

Early

Christianity and Political Power

"It was all about power," Teabing continued.

"Christ as Messiah was critical to the functioning of Church

and state. Many scholars claim that the early Church literally stole

Jesus from His original followers, hijacking His human message,

shrouding it in an impenetrable cloak of divinity, and using it

to expand their own power. I've written several books on the topic."

"And I assume devout Christians send you

hate mail on a daily basis?"

"Why would they?" Teabing countered.

"The vast majority of educated Christians know the history

of their faith. Jesus was indeed a great and powerful man. Constantine's

underhanded political maneuvers don't diminish the majesty of Christ's

life. Nobody is saying Christ was a fraud, or denying that He walked

the earth and inspired millions to better lives. All we are saying

is that Constantine took advantage of Christ's substantial influence

and importance. And in doing so, he shaped the face of Christianity

as we know it today."

(Chapter 55, pp. 133-34)

Here Brown has

Teabing assure Sophie that his distorted version of the history

of the Council of Nicea is actually unremarkable and that 'the vast

majority of educated Christians' would happily accept it. Not only

is it nonsense that any educated Christian would accept the fantasy

version of history Teabing relates, but any non-Christian with a

grasp of history would do so as well.

Constantine's

sponsorship of Christianity certainly did have a profound effect

on the development of that religion, but not in the way or for the

reasons that Brown's characters give.

Sophie glanced at the art book before her, eager

to move on and see the Da Vinci painting of the Holy Grail.

"The twist is this," Teabing said, talking faster now.

"Because Constantine upgraded Jesus' status almost four centuries

after Jesus' death, thousands of documents already existed chronicling

His life as a mortal man. To rewrite the history books, Constantine

knew he would need a bold stroke. From this sprang the most profound

moment in Christian history." Teabing paused, eyeing Sophie.

"Constantine commissioned and financed a new Bible, which omitted

those gospels that spoke of Christ's human traits and embellished

those gospels that made Him godlike. The earlier gospels were outlawed,

gathered up, and burned."

(Chapter 55, p. 134)

The idea that

'Constantine commissioned and financed a new Bible' is pure nonsense.

The canon of the Christian Bible was well established long before

Constantine was even born and does not differ in any substantial

way from the Bible used by Christians today ( see above).

Brown seems

to have derived the idea that Constantine 'commissioned' a 'new'

Bible from the fact that the Emperor did commission Eusebius to

oversee the production of fifty copies of the accepted 'scriptural'

texts - texts "of the sacred scriptures which you know to be

especially necessary for the restoration and use in the instruction

of the church." (Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 4.37)

This was not 'a new Bible', simply the production of fifty copies

of the Christian texts which had come to be considered 'Biblical'

long before Eusebius' and Constantine's time. The Emperor commissioned

and funded these copies not as part of some attempt to impose a

new collection of texts on Christianity but simply because, in an

age where book production was expensive and a copy of just one text

cost the modern equivalent of a new car, the production of fifty

full copies of all the already accepted texts was a massively expensive

undertaking.

Brown totally

misrepresents this enterprise as creating 'a new Bible', whereas,

in fact, the texts Eusebius oversaw had already been accepted for

over 150 years. These texts included the gospels of Matthew, Mark,

Luke and John, which had long been considered the oldest and most

authentic accounts of Jesus' life. These gospels actually emphasised

both Jesus' human aspects and his supposed supernatural nature and

they did not, as Brown claims, emphasise the latter over the former.

Many of the books the accepted canon rejected, on the other hand,

(such as the Gnostic works) portrayed Jesus was purely spiritual

and not human at all; despite Brown's claim that they presented

a 'more human' Jesus. On the contrary, they were actually rejected

largely because they portrayed a Jesus who was not human enough.

Once again, Brown gets his history backwards.

Back

to Chapters

Constantine

and 'Heresy'

"An interesting note," Langdon added.

"Anyone who chose the forbidden gospels over Constantine's

version was deemed a heretic. The word heretic derives from that

moment in history. The Latin word haereticus means 'choice.' Those

who 'chose' the original history of Christ were the world's first

heretics."

(Chapter 55, p. 234)

This claim is

incorrect. 'Heresy' does derive from a word meaning 'choice', 'a

thing chosen', 'an opinion (through choice)', but it is derived

from the Greek word 'hairesis'. The Latin 'haereticus'

is, in turn, derived from the Greek. It is not true, however, that

those condemned by the 'winners' at the Council of Nicea were somehow

'the world's first heretics', as Langdon asserts. The Greek word

was used to refer to rival sects within Judaism by the Jewish historian

Josephus, who used it as a term to describe the Saducees, Pharisees

and Essenes. It is also used to describe dissenting opinions within

Christianity in the New Testament of the Bible: in Acts 5:17, 15:5,

24:5, 26:5, 28:22, 1Corinthians 11:19 and Galatians 5:20. Irenaeus

wrote his book Adversus Haereses (Against Heresy) circa 180

AD and Tertullian wrote his De Prescriptione Haereticorum

(The Prescription Against Heretics) around 200 AD. Christian sects

rejected by mainstream Christianity were being referred to as 'heretics'

long before Constantine's time and the ones rejected after the Council

of Nicea were not Gnostics (as Brown implies) but Arians (who Brown

seems to know nothing about at all).

Back

to Chapters

Nag

Hammadi and the Dead Sea Scrolls

"Fortunately for historians," Teabing

said, "some of the gospels that Constantine attempted to eradicate

managed to survive. The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the 1950s

hidden in a cave near Qumran in the Judean desert. And, of course,

the Coptic Scrolls in 1945 at Nag Hammadi. In addition to telling

the true Grail story, these documents speak of Christ's ministry

in very human terms.

(Chapter 55, p. 234)

Leaving aside

the fact that there was no campaign by Constantine to 'eradicate'

non-canonical texts, this passage is riddled with errors. The first

of the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in 1947, with others found

between then and 1956. More importantly, the idea that the Scrolls

contained lost 'gospels' is complete nonsense: the Dead Sea Scrolls

are all purely Jewish texts, most of which were composed about 150

years before Jesus was even born. There are no 'gospels' in the

Dead Sea Scroll material simply because there are no Christian texts

amongst it at all - they are purely pre-Christian Jewish books.

The Nag Hammadi

texts are codices - an early form of sewn and bound book - not 'scrolls'.

They definitely do not tell anything which could be described as

'the true Grail story' and they certainly do not 'speak of Christ's

ministry in very human terms'. Most Gnostics actually believed that

Jesus was not a human at all and was a spirit who simply appeared

human. These texts in fact pour scorn on the idea that Jesus could

have been human in any way, since the Gnostics regarded the material

world and the physical body as the sinful products of the evil 'demiurge'.

The key aim of Gnosticism was to escape the physical and return

to the spiritual world after death and Jesus was a spirit sent to

help us achieve this. This is why, contrary to what Brown has Teabing

claim here, the Jesus of the Gnostic gospels is entirely unhuman,

other worldly and remote from human understanding. Unlike the canonical

gospels of the Bible, very little attention is paid in the Nag Hammadi

texts to the human aspects of Jesus' life - his friends, what he

did, where he went and what happened to him. Almost all their emphasis

is on his teachings, sayings and the gnosis or 'knowledge' he imparted

to help people escape from the physical world and its sinfulness.

So the Jesus

of the Nag Hammadi texts is not one depicted in 'very human terms'

at all. The truth is actually quite the opposite.

Of course, the Vatican, in keeping with

their tradition of misinformation, tried very hard to suppress the

release of these scrolls. And why wouldn't they? The scrolls highlight

glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications, clearly confirming

that the modern Bible was compiled and edited by men who possessed

a political agenda--to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ

and use His influence to solidify their own power base."

(Chapter 55, p. 234)

The idea that

'the Vatican' tried to suppress the release of any of this material

is pure fantasy. The first partial translation of the Nag Hammadi

texts appeared in 1956, but a full translation in English was the

result of the formation of the International Committee for the Nag

Hammadi Codices by UNESCO and the Egyptian Ministry of Culture in

1970. The first one volume translation was produced by James M.

Robinson and published as The Nag Hammadi Library in English

in 1977. A newer translation by Harvard scholar Bentley Layton was

published as The Gnostic Scriptures: A New Translation with Annotations

in 1987. Contrary to Brown's claim, 'the Vatican' or the Catholic

Church had no objections whatsoever to any of these publications.

Catholic scholars have been heavily involved in the UNESCO project

and copies of Robinson's and Layton's translations are readily available

on the shelves of Catholic bookshops.

Brown seems

to have got the idea that the Catholic Church tried to 'suppress'

these alternative gospels from The Dead Sea Scrolls Deception

by Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh. Like their better known earlier

work, Holy Blood Holy Grail, this book is a conspiracy theory

based on pseudo scholarship, leaps of logic and insinuation and

its claims have since been shown to be utterly false. Baigent and

Leigh maintain that the long delay in publishing the full texts

of many of the Dead Sea Scrolls was due to 'the Vatican' desperately

trying to suppress information in the Scrolls that would shake the

foundations of Christianity. The reality, however, is much less

dramatic.

While much of

the Dead Sea material was published fairly rapidly, the team responsible

for the texts from 'Cave 4' worked with remarkable slowness. This

team, led by the Dominican Father Roland de Vaux, was responsible

for 40% of the total Scroll material and the slow pace of their

work and their refusal to give other scholars access to the texts

caused anger amongst fellow academics, Catholic or otherwise. This

led Baigent and Leigh to assume the slow pace was actually a 'Vatican'

conspiracy and a deliberate attempt to suppress secret information

about Christianity found in the Cave 4 texts.

Their book came

out in 1991, but soon afterwards the academic stranglehold on the

Cave 4 texts was broken and other scholars were finally able to

analyse these scrolls. Not surprisingly, Baigent and Leigh were

totally wrong: there was no devastating information about Jesus

in these texts, in fact there was nothing in them about Jesus or

anyone to do with Christianity at all.

So not only

did 'the Vatican' not try to 'suppress' either the Dead Sea Scrolls

or the Nag Hammadi gospels, but there was nothing in either of these

collections of texts which was radical or (in the Dead Sea Scrolls

case) even relevant to early Christianity in any way.

Back

to Chapters

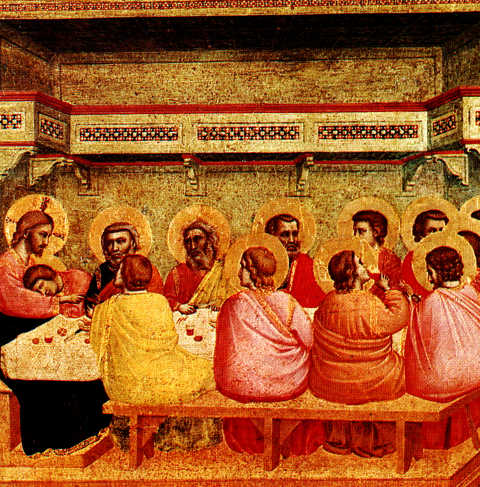

Leonardo's

The Last Supper

Teabing reached for the book and flipped toward

the center. "And finally, before I show you Da Vinci's paintings

of the Holy Grail, I'd like you to take a quick look at this."

He opened the book to a colorful graphic that spanned both full

pages. "I assume you recognize this fresco?"

He's kidding, right? Sophie was staring at the most famous fresco

of all time - The Last Supper - Da Vinci's legendary painting from

the wall of Santa Maria delle Grazie near Milan. The decaying fresco

portrayed Jesus and His disciples at the moment that Jesus announced

one of them would betray Him. "I know the fresco, yes."

"Then perhaps you would indulge me this little game? Close

your eyes if you would."

Uncertain, Sophie closed her eyes.

"Where is Jesus sitting?" Teabing asked.

"In the center."

"Good. And what food are He and His disciples breaking and

eating?"

"Bread." Obviously.

"Superb. And what drink?"

"Wine. They drank wine."

"Great. And one final question. How many wineglasses are on

the table?"

Sophie paused, realizing it was the trick question. And after dinner,

Jesus took the cup of wine, sharing it with His disciples. "One

cup," she said. "The chalice." The Cup of Christ.

The Holy Grail. "Jesus passed a single chalice of wine, just

as modern Christians do at communion."

Teabing sighed. "Open your eyes."

She did. Teabing was grinning smugly. Sophie looked down at the

painting, seeing to her astonishment that everyone at the table

had a glass of wine, including Christ. Thirteen cups. Moreover,

the cups were tiny, stemless, and made of glass. There was no chalice

in the painting. No Holy Grail.

Teabing's eyes twinkled. "A bit strange, don't you think, considering

that both the Bible and our standard Grail legend celebrate this

moment as the definitive arrival of the Holy Grail. Oddly, Da Vinci

appears to have forgotten to paint the Cup of Christ."

(Chapter 55, pp.235-36)

The idea that

a painting of the Last Supper should depict 'the Holy Grail' only

makes sense to someone with little or no knowledge of the artistic

conventions of Leonardo's period. Contrary to what Sophie expects,

no painting of the Supper in this period should be expected to always

depict a single large 'chalice' or any 'Holy Grail'. Some paintings

did so, especially if they were of the earlier episode where Jesus